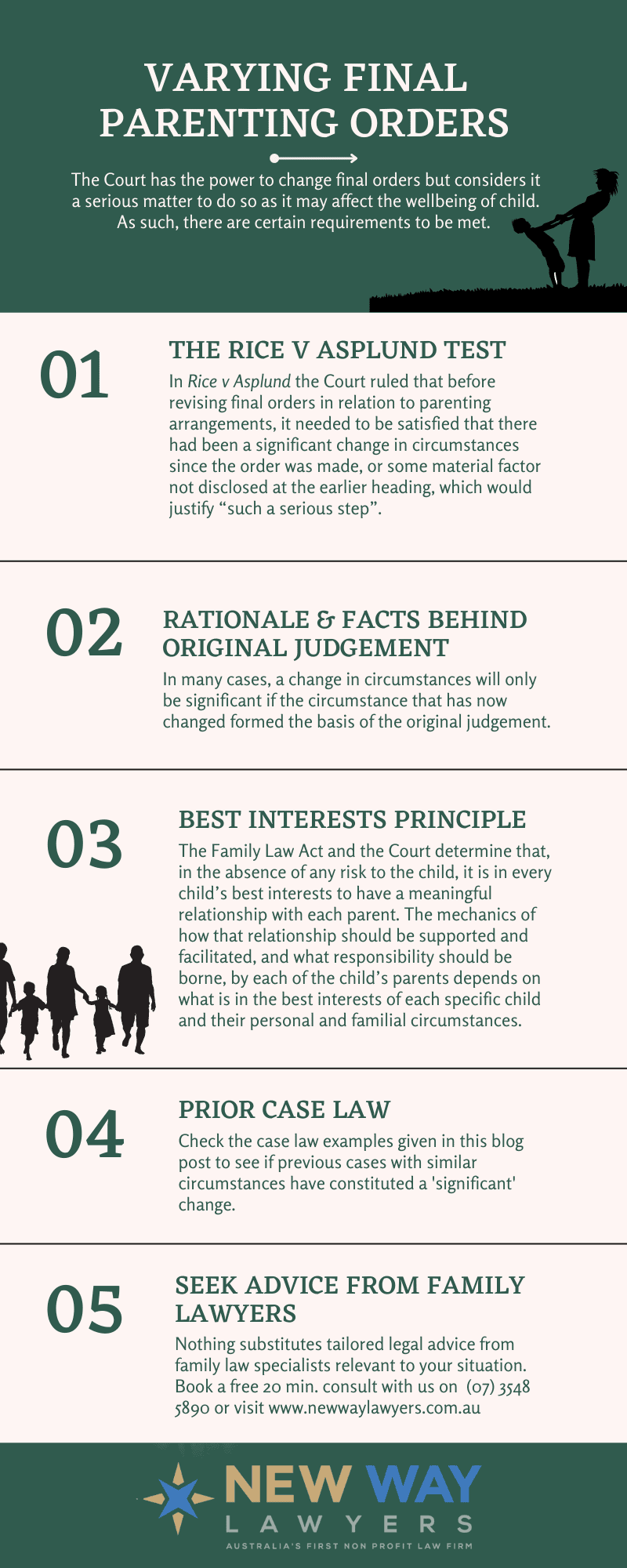

The Court will vary final parenting orders only in limited situations, where there has been a significant change in circumstances of the child or the family, or if it would be in the best interests of the child. If the Court decides to re-open a matter, this will likely result in fresh proceedings and new Orders being made upon the hearing of the issues in dispute.

The Rice v Asplund test

The case of Rice v Asplund (1979) set a threshold test for ascertaining whether or not a Final Order can be changed. In Rice v Asplund the Court ruled that before revising final parenting orders, it needed to be satisfied that there had been a significant change in circumstances since the order was made, or some material factor not disclosed at the earlier heading, which would justify “such a serious step”.

The rationale behind the rule

Chief Justice Evatt stated that the Court: “…should not lightly entertain an application … To do so would be to invite endless litigation for change is an ever present factor in human affairs .” This rule was created to protect children from being exposed to the uncertainty of ongoing litigation. This intent was further expressed in Freeman (1986) where Strauss J commented on the certainty of orders and the importance of supporting them to encourage “stability in the lives of children … an essential prerequisite to their well-being”. This ruling was a manifestation of the best interests of the child principle, as outlined in the Family Law Act (1975).

What is a significant change of circumstances?

What amounts to a significant change in circumstances depends on the individual situation. In some situations, an event or occurrence may amount to a significant change in circumstances but in another situation the same type of event or occurrence may not.

Some examples where the court has determined there to be a significant change of circumstance include:

- A party is seeking to relocate with the children;

- The parties have since consented to new parenting arrangements (e.g. entered into a parenting plan) and therefore, the current orders are no longer reflective of the actual arrangements for the children;

- A substantial period of time has elapsed between the final orders being made and the application being brought;

- One or more of the parties has re-partnered;

- There has been abuse of the children;

- A party to the proceedings or the child is in ill-health.

- The current orders were made without all the relevant information being before the court.

Other specific examples include:

-

- Psychological and physical changes in children as they grow up;

- The child has matured and changed their views on the current parenting orders;

- A parent has, by their own choice, spent no time with the children for over a year;

- A parent’s employment has changed, and they are able to spend more time with the children; and

- Conflict between the parents has risen to the point where the current orders are unworkable.

Book your free 20 minute consultation with one of our experienced family lawyers today on 1300 043 984.